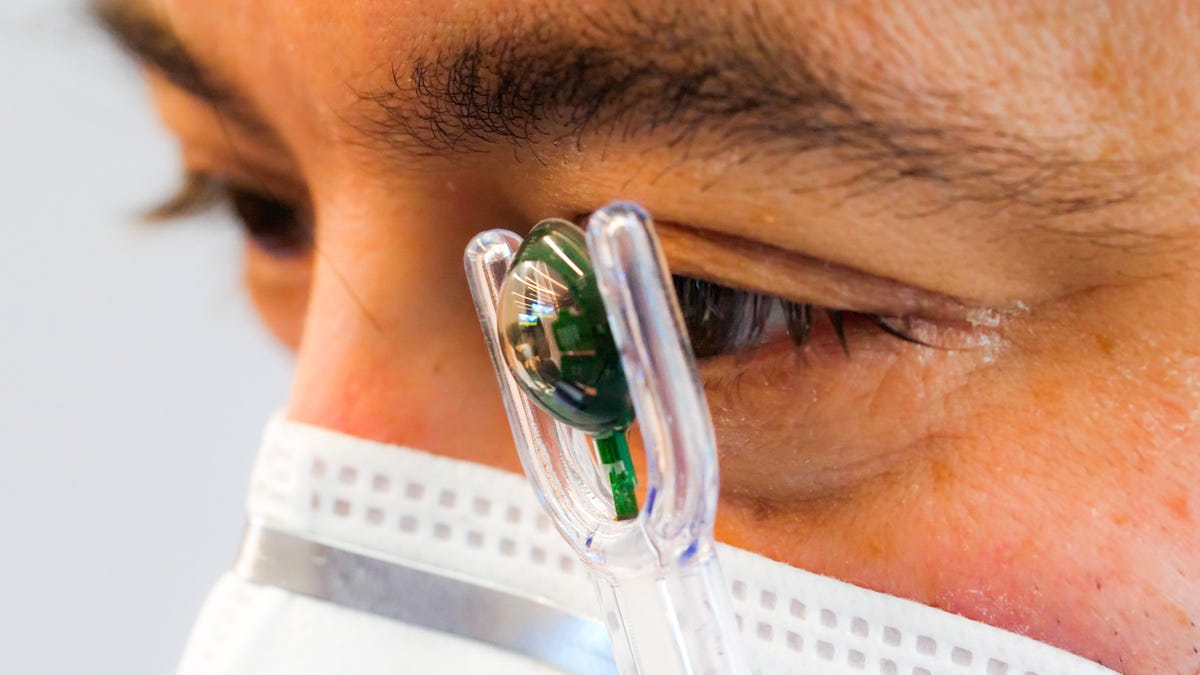

A series of pop-up directional markers appear, in tiny green lines across my vision. As I turn, I can see which direction north is. These are markers on a compass, projected on a little MicroLED display, perched on a contact lens, held in front of my eye on a stick. After years of trying on smart glasses, my return to looking at things through a curved lens the size of my fingernail felt just as wild as ever. I’m still not sure about wearing it in my eyes, though.

The Mojo Lens, a self-contained display-enabled lens that I previously tried in an earlier iteration before the pandemic at CES 2020, is back in a form that the company says is finally ready for internal testing.

I tested Mojo Vision’s latest prototype lens in an office building in midtown Manhattan a few weeks ago, as the company was preparing for its next phase of internal development. While Mojo’s contact lenses are still not approved for everyday use, these lenses are another step down the path, and represent the company’s completed tech package for what will be included in version 1.0.

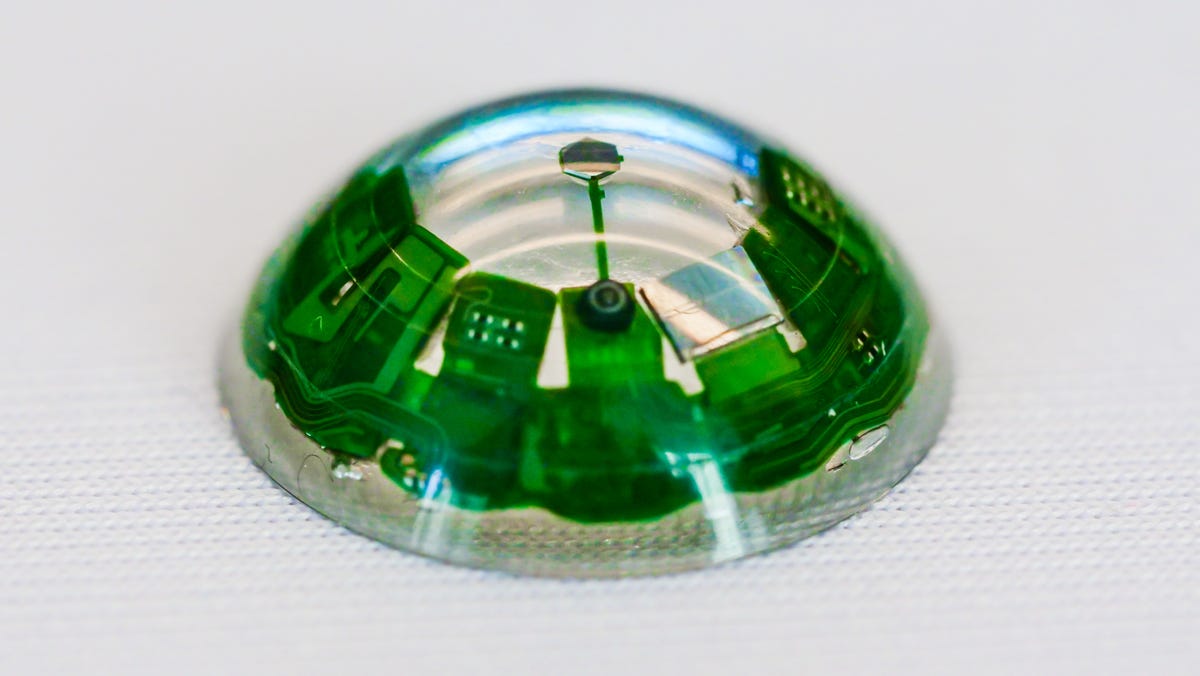

Mojo Vision’s technology is, in a sense, augmented reality. But not in the way you might be thinking of. The hard lens’ monochrome green display can show text, basic graphics and even some illustrations, but is designed to function more like a smartwatch. The lens’ accelerometer, gyro and magnetometer also give it something I didn’t get to try before: eye tracking.

The lens’ display is the green dot in the middle. That’s it. The ring of hardware around the edges are the motion-tracking and other chip components.

A world in your eyes

Unlike eye tracking tech in VR and AR glasses, which uses cameras to sense eye movement, these lenses follow eye movement by actually sitting on your eye. The sensors, like on a smartwatch, can calculate that movement more accurately than VR or AR glasses can, according to Mojo Vision’s executives. I didn’t actually wear these in my eyes, since the lenses aren’t cleared for wearing quite yet. I held the lens very close to my eye, and moved my head around to see the tracking effect.

When I tried Mojo’s lens back in 2020, it was a version that didn’t have the onboard motion-tracking tech, or any batteries. The new version has a battery array, motion tracking and short-range wireless connectivity.

But the lens isn’t a standalone device; a custom wireless connection communicates directly with an additional neck-worn device, which Mojo calls a relay, that will act as the companion computer for the lenses. I didn’t get to see that part of the Mojo Vision hardware, only the lenses.

The lenses are made to wirelessly connect with a local device, keeping motion-tracking and display elements on the lens itself.

The lenses won’t connect directly with phones right now, because the lenses needed a more power-efficient short-range wireless connection. “Bluetooth LE was too chatty and power hungry,” says Mojo Vision’s SVP of Product, Steve Sinclair, who walked me through the latest demos. “We had to create our own.” Mojo Vision’s wireless connection is in the 5GHz band, but Sinclair says the company still has work to do to make sure the wireless connection doesn’t receive or cause interference.

“A phone does not have the radio that we require,” Sinclair says. “It needs to be somewhat near the head because of the transmit power of the lens.” He says the tech could be built into a helmet, or even glasses, but right now a neckband-type device made the most practical sense.

Mojo’s aiming for longer-range connections in the future, ideally. The neck-worn processor will be able to connect to phones, though. It pulls GPS off phones and uses the phone’s modem for connectivity, making that neckband a bridge.

How I looked through the lens, moving my head around. Not quite the same as wearing one, but as close as I can get for now.

Navigating a tiny interface

Lifting my head and looking around the room with a lens on a stick in front of my face isn’t the same as wearing an eye-tracking, display-enabled contact lens. Even after this demo, the actual experience of wearing Mojo Vision’s lenses in the wild remains an unknown. But even compared to my last Mojo demo in January 2020, getting to see how the interface works on-lens makes the experience feel a lot more real.

In many ways, it’s reminiscent of a pair of smart glasses called Focals made by North, a company Google acquired in 2020. North Focals projected a small LED display in-eye that worked like a tiny readout, but didn’t have eye tracking. I can see how glancing around the lens can bring up pieces of information, very much like a smartwatch on my head, or like Google Glass… except different, too. The bright display hangs in the air like etched light, then vanishes.

I see a ringlike interface, something I saw simulated in 2020 on an eye-tracking Vive Pro VR headset when I last visited Mojo Vision in Las Vegas. I can see a small reticle that lands on small app icons around the ring, and staying on one for a few seconds opens it up. The ring around the periphery of my vision remains invisible until I look over at the edges, where app-like widgets appear.

I see a travel app, which simulates looking up plane flight information, and a tiny graphic that shows where my seat is. I can glance over at other windows (my Uber ride info, my gate). Another app-like widget shows what it would look like to see pop-up fitness data on the display (heart rate, lap information, like a smartwatch readout). Another widget shows images: I see a tiny baby Yoda (aka Grogu), rendered in shades of green. Also, a classic Star Wars shot of Han Solo. These images show that the display looks good enough to view pictures and read text on. Another, a teleprompter, rolls off text I can read out loud. When I glance away from the apps, back to the outer ring, the heads-up info disappears again.

It’s not easy to figure out how to move exactly right, but I’m not even trying these lenses the way they’re intended. In my eyes, they’d move as my eyes move, controlling the interface directly. Outside of my eyes, I have to tilt my head up and down. Mojo Vision promises the experience on-eye will make the display feel even more present, filling my field of vision. It makes sense, since I’m holding the display off my eye a bit. The lens’ display is meant to sit right on top of where my pupil would be, and its narrow display window lines up with the area that the fovea, the most detail-rich part of the center of our vision, would be. Glancing back outside the ring is meant to close an app, or open up another one.

The next version of the lens is aiming for an iris-like cosmetic design, plus prescriptions.

Next step: Actually wearing it; then, prescriptions

The Mojo Vision lens I’m looking at now definitely has more onboard hardware than the 2020 version I previously saw, but it’s still not all fully activated yet. “It’s got a radio, it’s got a display, it’s got three motion sensors, it’s got a host of batteries built into it and the power management system. It’s got all those things in there,” Sinclair tells me. But the power system on the lens has not been activated yet to work in-eye. Instead, right now, the lens is attached to a small arm bracket I hold while power’s delivered to it. For the moment, the demo I try is using the wireless chip to pull data on and off the lens for it to display.

The Mojo Lens has a small Arm Cortex M0 processor on the lens itself, which handles encrypted data running on and off the lens, and power management. The neck band computer will run the applications, interpret eye tracking data and update image placement in 10-millisecond loops. While in some ways the graphic data isn’t intense (it’s a “300-pixel diameter of content,” says Sinclair), the processor will need to keep updating this data quickly and reliably. If things go out of sync, it could get disorienting on an eyeball pretty fast.

The company’s timeline for lens prototypes. I tried the 2019 model (on a stick) last time.

Mojo Vision’s CEO, Drew Perkins, will wear the lens in-eye first. Then the company’s other executives will, Sinclair says, and the rest of their executive team sometime after that. The company’s fitness and sports partnerships announced earlier this year are designed to open up some early testing to see how the lenses might work with fitness and sports training applications.

Mojo Vision is also working on having these lenses work as medically approved assistive vision devices, but those steps may still be further down the line. “We could imagine low-vision users having a second higher-resolution camera built into a pair of glasses, or hanging over their ear — they look at something and it takes a really high-resolution picture and then it just appears in their eyes, and then they can pan and zoom and see things,” Sinclair says about the future. Mojo Vision’s not there yet, but testing these eye-tracking wearable microdisplays is going to be the start.

Also, these lenses are going to need FDA clearance as contact lenses, a process Mojo Vision is working on. They’ll also need to be made in various prescriptions, and the company aims to shield the chip hardware with an artificial iris to make the lenses seem more normal-looking.

“We have work to do to make it a product. It’s not a product,” Sinclair emphasizes about where the Mojo Vision lenses are at. I’d be pretty nervous about being the first person to try in-eye testing of these lenses, but why wouldn’t I be? This type of tech has never existed before. Only one other company I know of, InWith, is working on smart contact lenses. I’ve never seen any demos of how those competing soft lenses will work, and those don’t seem to have displays yet. The frontier of tiny wearable displays makes previously bleeding-edge smart glasses seem old-fashioned in comparison.

link